|

Email a link to this page to someone who might be interested. Internet Explorer is the only browser that shows this page the way it was designed. Your computer's settings may alter the display.

April 24,

2004: Awarded "Best Web Site of the Year" by the Illinois State Historical

Society

|

|

|

Marquee Lights of the Lincoln Theater, est. 1923, Lincoln, Illinois |

|

|

|

Pictorial Supplement to a

Reassessment

|

|

commemorating Lincoln's 1854 Peoria

speech: bust

portion of

|

|

|

On October 4, 1854, Abraham Lincoln delivered a major political speech in Springfield, Illinois, as a response to a speech that Stephen A. Douglas had given there the day before. On October 16 Lincoln repeated a somewhat longer version of this speech, then revised it for publication to reach a wider audience. Known as the Peoria speech, it presented the main antislavery positions and arguments, including criticisms of Douglas, that became the foundation of Lincoln's second political career, which led to his presidency. Background After Abraham Lincoln's single term in the US House of Representatives ended in 1849, he returned to Springfield and resumed his legal career, with considerable success. He played no major role in Illinois politics at first, but he did deliver a couple of noteworthy political speeches, and he followed national politics by reading newspapers. In 1850 Lincoln gave an invited eulogy for Whig President Zachary Taylor, and in 1852 Lincoln delivered a more significant eulogy for the Whig Congressman Henry Clay, Lincoln's political hero. Also in 1852, Lincoln delivered a political speech to the Scott Club of Springfield in which he supported the Whig presidential candidacy of Winfield Scott, a Mexican War hero. Much of that speech was a vigorous, legalistic refutation of a speech by Stephen Douglas, who supported the Democratic presidential candidate, Franklin Pierce. In 1854 Lincoln re-entered national politics, because like many of his contemporaries, he was deeply troubled by the enactment of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, which repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and opened the way for slavery to spread to new territories. US Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln's political opponent in the 1830s, had used his considerable power in Congress to pass the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, which was signed by Democratic President Buchanan in May 1854.

The Peoria speech is one of

several I discuss in “Classical Rhetoric as a Lens for Reading the Key

Speeches of Lincoln’s Political Rise, 1852–1856," Journal of the

Abraham Lincoln Association (Winter 2014) (link to full text of it

below under Suggest Sources for Browsing and Research). Various

discussions of those speeches appear in the vast Lincoln literature, but

my article explains the rhetorical qualities of these

speeches more thoroughly than previous scholarship, and I adapted that article as

chapter 4, "Introducing Arguments against Slavery and Stephen A.

Douglas," in my book titled Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence: How He

Gained the Presidential Nomination:

https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/?id=p088032; also at

Amazon,

https://www.amazon.com/Lincolns-Rise-Eloquence-Presidential-Nomination/dp/0252045947. |

|

|

In the context of critiquing previous scholarship, my rhetorical/textual analysis of Lincoln's compositions--speeches and other writings--in Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence explains their fundamental communicative elements--in chapter 4 Lincoln's speeches just before, during, and after he began his celebrated, second political career in 1854: the 1852 eulogy on Henry Clay, the 1852 Scott Club speech, the 1854 Peoria speech, four 1856 campaign stump speeches, and the 1856 banquet speech in Chicago. Additional Historical Background In the fall of 1854, Lincoln became a candidate for the Illinois state legislature, and he later aspired to the US Senate. In those days state legislatures chose their US Senators. In the fall of 1854, Lincoln began to follow Douglas as he delivered stump speeches in various central Illinois communities, and Lincoln's speeches were lawyerly refutations of Douglas's defense of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. These 1854 speeches were the first Lincoln-Douglas debates, but they were not joint debates, as were the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. Lincoln's most famous speech in this series was given October 4 at Springfield and repeated about two weeks later in Peoria, including criticism of Douglas's rebuttal of Lincoln's October 4th Springfield speech. In preparing the Springfield-Peoria speech, Lincoln conducted research in the Illinois State Library in the Statehouse, and the speech was well crafted with elements of classical rhetoric.

The

Peoria speech presents the central legal, historical, and moral

arguments that Lincoln used to oppose slavery and its extension

throughout his second political career. As he

did for many of his political speeches, Lincoln carefully revised the Peoria speech for newspaper publication, which

greatly expanded the public's familiarity with his arguments. |

John McClarey's bonded bronze statuette on a walnut base, in the author's collection of Lincolniana, purchased directly from the sculptor

|

|

Early in 1855 Lincoln failed to get

enough support in the Illinois legislature for it to elect him to the US

Senate, so he used his

influence to get the antislavery Democrat Lyman Trumbull elected.

Lincoln persevered with his ambition to rise in national politics.

Senator Trumbull later became a Republican--one of Lincoln's many

political allies. Lincoln’s return to the political arena led him to help

establish the Illinois Republican Party in 1856. His party leadership in

turn led to the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, which gave him national

recognition, then to his 1860

presidential nomination and election. |

|

|

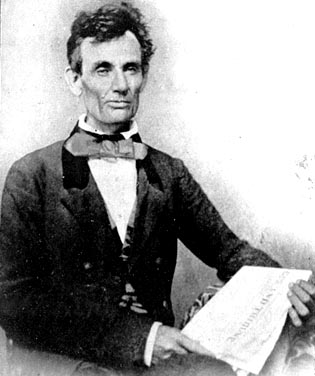

Lincoln in 1854 |

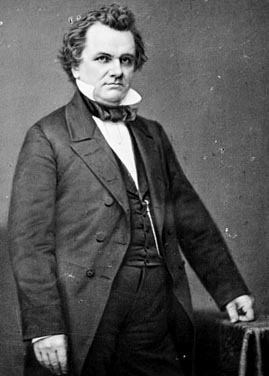

Douglas in the mid 1850s |

|

photos from the Library of Congress |

|

|

The communicative elements in Lincoln’s political speeches trace to classical rhetoric—the work of Greek and Roman writers who established the field of study dealing with the theory, practice, and instruction of discourse. Familiarity with classical rhetoric enables readers to gain a better understanding of how Lincoln deployed the full range of rhetorical strategies and language techniques to suit his political purposes and audiences.

Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence identifies sources of classical rhetoric that may have influenced him, including textbooks and anthologies he read while growing up in Indiana and reaching young adulthood at New Salem, and especially the speeches of Senator Daniel Webster that Lincoln studied in adulthood. Webster's substantial, formal education included the study of classical rhetoric. Biographers and historians have long identified Lincoln's interest in Webster's oratory, but studies of how Webster's speeches influenced Lincoln's rhetoric have been limited. Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence identifies specific parallels between Webster's and Lincoln's speeches, including their language, that suggest Webster's influence. Lincoln was also greatly influenced by Henry Clay's political positions and speeches, but Clay lacked education in classical rhetoric.

Key speeches of Lincoln’s second political career refute Stephen A.

Douglas’s main political position--popular sovereignty--that local

governments in new territories should decide whether to allow slavery.

Lincoln argued that slavery is a national, not a local, problem and

should be handled by Congress. Lincoln found the solution to the slavery

controversy rooted in

the principle of the Declaration of Independence that “all men are

created equal.” Lincoln was always a proponent of the natural rights of

black people, but in the 1850s did not favor social and political equality

between the races. (Late in his presidency he became more receptive to

extending civil rights to educated black men.) Beginning in 1854, Lincoln argued that slavery should be confined to

Southern states, where the Constitution allowed it and where it would

eventually die out. |

|

|

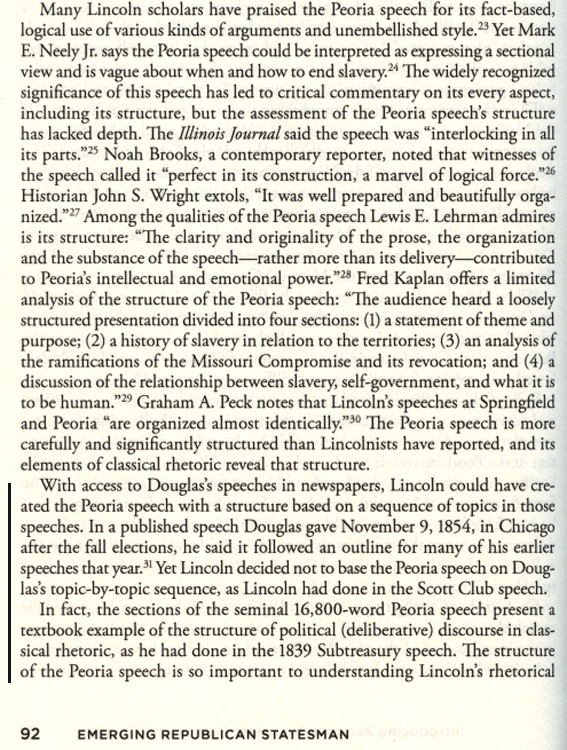

My analyses of Lincoln’s compositions pay close attention to their organizational strategies. Lincoln’s two-hour, 1854 Peoria speech--the first of his second political career--is a textbook example of how to organize a political speech according to classical rhetoric, just as was his last major speech in the Illinois legislature is an earlier example--the 1839 Subtreasury speech. Despite extensive scholarship on Lincoln's Peoria speech, consideration of its organization has been lacking, as noted in chapter 4 of Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence:

Appropriate organization is a key strategy in achieving an effective message in any genre. A political composition organized in the tradition of classical rhetoric uses a formal introduction (exordium), a "statement of facts" section, refutation of opposing arguments, explanation/justification of the writer/speaker's positions/solutions to a problem or controversy, and a formal conclusion (peroration). Most of Lincoln's other formal compositions demonstrate a flexible use of classical organization to suit his message and audience. Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence offers a twelve-page, fresh analysis of the Peoria speech, including its context, purpose, organization, methods of argumentation and refutation, emotional appeals, sentence construction, and plain and literary language. Lincoln’s political rhetoric benefited from his legalistic ability to expose contradictions, fallacies, and lies in the speeches of his opponents. In his first political career, Lincoln sometimes cruelly attacked rivals and other political opponents, but in his second political career, he was more judicious with using that technique, because he was conflicted about it. The antislavery moral stance that Lincoln expressed in the Peoria speech included criticism of Douglas's demagoguery. In the 1830s Lincoln had attacked Douglas for lying, At the beginning the Peoria speech, Lincoln said he would refrain from personal attacks, yet Douglas's false claim that Lincoln favored social and political equality between black people and whites outraged Lincoln: "If a man will stand up and assert, and repeat, and re-assert, that two and two do not make four, I know nothing in the power of argument that can stop him. I think I can answer the judge so long as he sticks to the premises; but when he flies from them, I cannot work an argument into the consistency of . . . a gag, and actually close his mouth with it."

In the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas

debates, the rivals accused one another of lying and other rhetorical

abuses, and Lincoln had to decide whether or how to use personal

attacks against his fiery, demagogic rival. Chapter 7 of Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence

pays close attention to this dilemma and reveals its resolution.

|

|

|

Lincoln's legal and political writing and speaking show

the importance of rhetorical knowledge and skill. Many of today's

undergraduate and graduate degree programs offer required or elective

courses that include the study of fundamentals traced to classical

rhetoric, for example, courses in business communication,

professional/technical communication, marketing communication, and

speech communication. Today's students preparing for careers in the

professions, business, industry, and nonprofits would benefit from the study of writing models that embody

fundamentals derived from classical rhetoric, just as Lincoln did. |

|

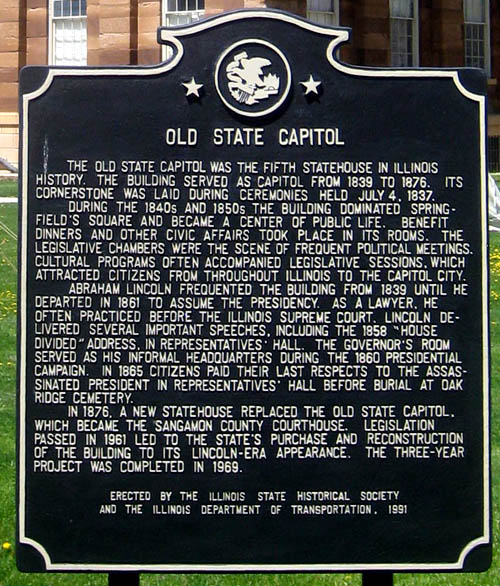

Photos Relating to Lincoln's Political Speeches in the Illinois Statehouse Abraham Lincoln gave the first version of his Peoria speech in the Representatives chamber of the Illinois Statehouse (Capitol) on October 4, 1854, the day after Douglas had given a political speech there. The Statehouse was across the street from the building with the Lincoln-Herndon law offices. Sculptor Larry Anderson assigned the date of October 4, 1854, to his work titled Springfield's Lincoln, as seen below. Representatives hall was also the location where Lincoln delivered his 1858 speech accepting the unanimous Illinois Republican party nomination for the US Senate--the famous, provocative House Divided speech. On June 4, 2004, as my wife and I traveled through Springfield, Illinois, we visited the Old State Capitol Plaza, including Dr. John Paul's famous Prairie Archives bookstore there. At the Plaza we serendipitously witnessed the late, lamented Larry Anderson supervising the installation of his Lincoln family life-size, bronze statues. They depict the Lincolns on October 4, 1854, when Mr. Lincoln delivered a three-hour, 17,000-word antislavery speech in the Illinois Capitol that he also delivered at Peoria on October 16. Known as the Peoria speech, it launched his second political career, leading to the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates and his 1860 election to the presidency. Unless otherwise noted, the photos below were taken by my wife, Pat, or me.

At the moment the photo below was taken, the statue of William Wallace ("Willie") Lincoln, age three, had not yet been installed, in front of his parents. The Lincolns' last child, Thomas ("Tad"), was logically excluded from this statue group, because in October 1854 he was just over a year old.

Below, Larry Anderson's Springfield's Lincoln on October 4, 1854, in front of the Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices, with son William Wallace ("Willie") Waving to his older brother, Robert (and to the contemporary boy in the orange shirt)

Mary Lincoln adjusts her husband's apparel just before he enters the Statehouse, where he delivers the first version of the Peoria speech in Representative Hall.

Fifth Illinois Statehouse (1839--1876): where Lincoln delivered the first version of the Peoria speech and the 1858 House Divided speech, and where his body lay in state in 1865. Capitol photos by the author and his wife, April 26, 2014.

Below: on the first floor of the Statehouse, the State Library provided key resources Lincoln used to research his 1854 Peoria speech and others.

stairs to the second-floor chambers of the House of Representatives and state Senate

statue of Stephen A. Douglas at Representative Hall entrance For a brief time in the late 1830s, Douglas and Lincoln served in the Illinois House of Representatives together. In these chambers on October 3, 1854, Douglas delivered a speech defending his support for the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, including popular sovereignty, and Lincoln responded the next day in the same location--the first version of his celebrated Peoria speech.

The Douglas photo above is not clear enough to show that the index finger of

the right hand is missing. That peculiarity had been written about by my

Lincoln literature professor at Lincoln College, James T. Hickey:

above, portrait of Lincoln's exemplar George Washington in Representative Hall. Below, the desktops have candlesticks, ink wells, and quill pens.

From the balcony visitors could observe proceedings and speeches. Source: Illinois Guide to State Historic Sites and Memorials (Illinois Historic Preservation Agency) Photos and Other Visuals Related to the Peoria Speech (in Peoria)

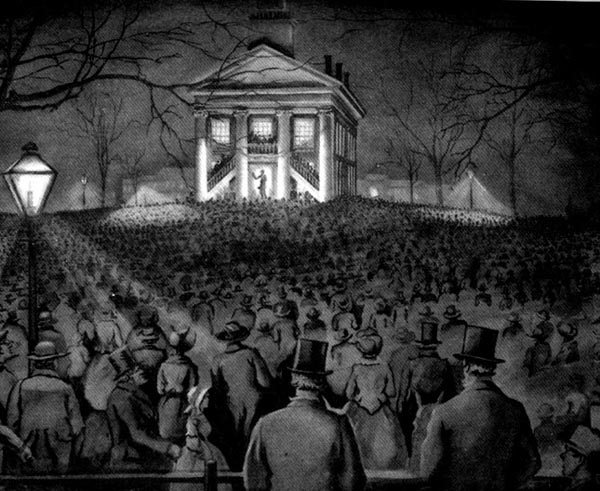

Peoria Courthouse, 1835--1876, adapted from B.C. Bryner, Abraham Lincoln in Peoria, Illinois (1924)

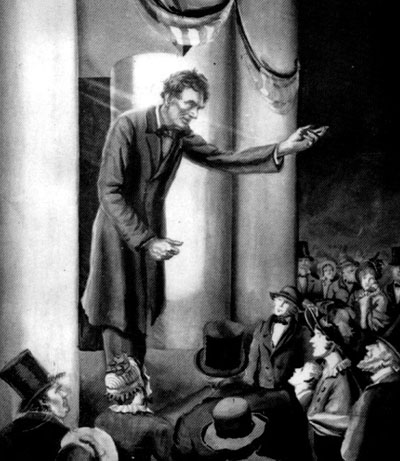

Charles Overall's painting of Lincoln delivering the Peoria speech at night, adapted from B.C. Bryner, Abraham Lincoln in Peoria, Illinois (1924) During the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, on October 5, two days before the fifth joint debate, at Galesburg, Lincoln traveled about ten miles from Peoria down the Illinois River by steamer to Pekin, where he delivered a lengthy stump speech in the afternoon. The legendary riverboat captain Henry Detweiller invited Lincoln onto his steamer to return him to Peoria. They rode on the hurricane deck. (The Lincoln Log, https://thelincolnlog.org/Home.aspx). No text of that speech has been found.

Charles

Overall's painting of Lincoln speaking on |

|

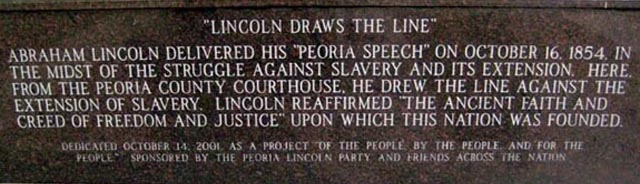

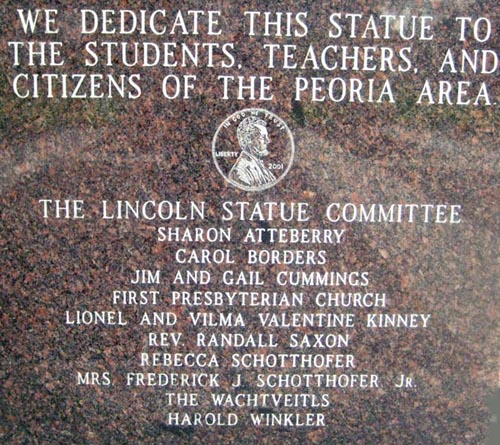

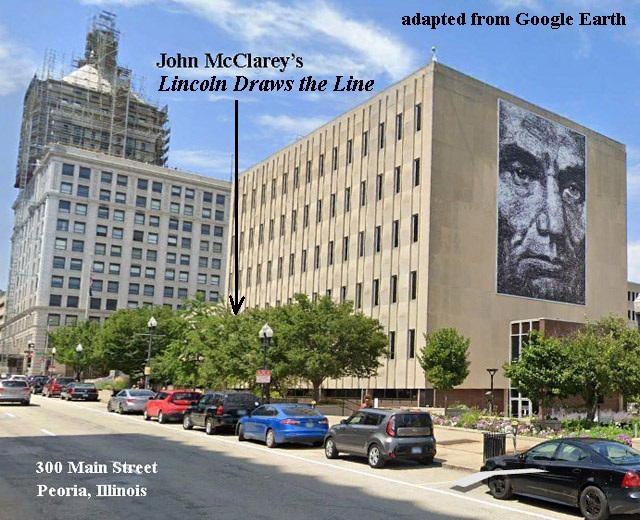

author's photo of John McClarey's

Lincoln Draws the Line

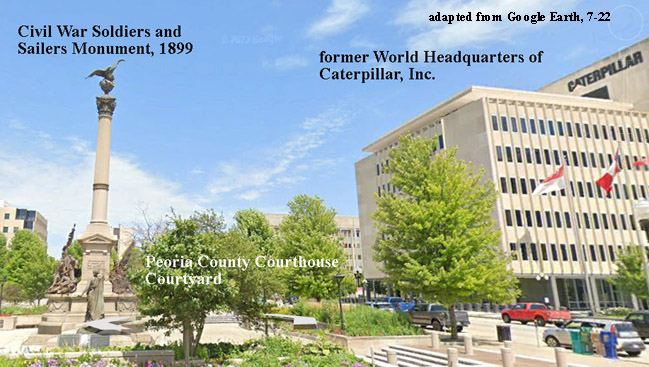

I am proud to say that I am one of the teachers referred to on this plaque: for thirty years I taught high school English at Pekin, a suburb of Peoria and the seat of Tazewell County. Abraham Lincoln engaged in politics and practiced law in Pekin, on the Eighth Judicial Circuit. Above photos by the author. John McClarey's Lincoln Draws the Line is located on the northwest section of the Peoria County Courthouse block. In the screen capture below, the large Lincoln picture faces the Peoria County Courthouse courtyard, on the east side of that block.

Below: The Peoria County Courthouse courtyard has several war memorials, in addition to the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Across the street from the Peoria County Courthouse courtyard is the former World Headquarters of Caterpillar, Inc. (As a retired English teacher, I put a comma after Caterpillar, but the company does not use a comma before Inc.) In the fall of 1986, one of my business contacts, a Caterpillar retired copywriter and in-house editor, arranged for me to conduct a series of eighteen, one-hour writing workshops at the Caterpillar World Headquarters. In 1990 I partnered with a technical writer and a technical illustrator, both former Caterpillar employees, to form Technical Publication Associates, Inc., and Caterpillar was one of our most important clients.

The Author's Other Research-based Lincoln Projects In 2004 the Illinois State Historical Society gave a Superior Achievement Award to my collaborative, community history website of Lincoln, Illinois (findinglincolnillinois.com). In 2008–09 I was an honorary member of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission of that town. I researched and wrote the play script for the 2008 re-enactment of the 1858 Republican "monster" rally there the day after the last Lincoln-Douglas debate, at Alton--so far away from the town of Lincoln that he had to travel by train during the night to get there. Lincoln delivered a stump speech at the rally, but no copy of it has been found. My play script features a research-based, “reasonable facsimile” of that rally and speech, including give-and-take with the audience. The re-enactment was accomplished through collaboration with the late, lamented Paul Beaver, professor emeritus of history at Lincoln College and author of several local histories; Ron Keller, professor director of the Lincoln Heritage Museum; and Wanda Lee Rohlfs, civic leader. Links to the play script of the re-enactment and a photo album and video of it appear below under Sources Suggested for Browsing and Research. In 2008 I proposed erecting a statue of Abraham Lincoln as the 1858 Senate candidate and a corresponding historical marker, both to be installed on the lawn of the Logan County Courthouse, where the 1858 rally and 2008 re-enactment of it took place. Since then, a local committee raised funds to fulfill those proposals. In 2012 my book titled The Town Lincoln Warned: The Living Namesake History of Lincoln, Illinois, received a Superior Achievement Award from the Illinois State Historical Society. In 2013 I proposed several additional statues of Lincoln at Lincoln to expand its namesake heritage, strengthen civic pride, and increase heritage tourism (link to the webpage of that proposal below under Suggested Sources for Browsing and Research). Also in 2013 the Lincoln Elementary School District honored me as one of four distinguished alumni. Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence is the capstone of my Lincoln-related research and publication. I share information about technical and marketing communication, my Abraham Lincoln research, American literature, Illinois history and historic preservation, and heritage tourism on Facebook and LinkedIn. Origins of the Author's Interest in Abraham Lincoln The Lincolnian seed planted in me as a child and young adult lay dormant for almost forty years. It did not germinate until after I was in the middle of my second teaching career, at Missouri State University. Then, I became curious how my hometown of Lincoln, Illinois--the first Lincoln namesake town--had shaped me, so I began to research it and write about it. Accordingly, Abraham Lincoln stepped out of the shadows, and I became a fourth-generation link in a chain of historians and Lincoln buffs from Logan County, Illinois. My mother, Jane Wilson Henson, had told me of Lincoln practicing law in the Postville Courthouse (that site, a block away from the Henson family home, was one of my playgrounds) and of Lincoln's recreation in Postville Park (down the block from the Wilson family home, a favorite Wilson-Henson playground and site of family reunions). In the 1950s, as an elementary school student at Jefferson School (two blocks from the Postville Courthouse site), I heard stories of the Lincoln legend told by E.H. Lukenbill, a well-known Lincoln buff and beloved county superintendent of schools. My interest in Abraham Lincoln further stems from a course I took as a freshman at Lincoln College in 1960–61. That course on Lincoln’s life and times was taught by the renowned Lincoln historian James T. Hickey. The textbook was Abraham Lincoln: A Biography by the legendary Benjamin Thomas. (Some say that book endures as the best one-volume Lincoln biography.) For many years Mr. Hickey was the curator of the Lincoln Collection at the Illinois State Historical Library, now part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Mr. Hickey taught with authoritative knowledge of Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, and with a charming wit. In addition, Mr. Hickey spoke in the Lincolnian tradition of telling humorous stories. Mr. Hickey's research on Lincoln was published as The Collected Writings of James T. Hickey (Springfield, IL: the Illinois State Historical Society, 1990). Mr. Hickey was a protégé of Judge Lawrence B. Stringer, author of the encyclopedic History of Logan County, Illinois, 1911. It features a chapter on Abraham Lincoln’s legal and political activity in central Illinois that has been cited by Lincoln biographers. I often cite Judge Stringer's book in findinglincolnillois.com. Judge Stringer drew upon the reminiscence of Robert B. Latham, one of the three founders of Lincoln, Illinois. Abraham Lincoln was the attorney for the town’s founders, the town being established in 1853, the year before the Peoria speech and before Lincoln started to become famous. Latham was also a founder of Lincoln University (1865)--the first Lincoln namesake institution of higher education--renamed Lincoln College, now closed. Latham was a personal and political friend of Abraham Lincoln and a Union colonel in the Civil War. Judge Stringer's Lincolniana provided the core material that established the Lincoln Heritage Museum of Lincoln College. Lincoln College is closed, but the Lincoln Heritage Museum remains open in 2024, under the direction of civic leader and Lincoln expert Ron J. Keller, author of Lincoln in the Illinois Legislature (Southern Illinois University Press).

D. Leigh Henson Please consider sharing a link to this webpage with anyone interested in Abraham Lincoln, his first namesake town, political discourse, or the history of Springfield or Peoria, Illinois. Also access and share links to sites where Lincoln's Rise to Eloquence: How He Gained the Presidential Nomination is available for purchase: https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/?id=p088032 and https://www.amazon.com/Lincolns-Rise-Eloquence-Presidential-Nomination/dp/0252045947. Suggested Sources for Browsing and Research Basler, Roy P., et al., eds., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/?key=title;page=browse Bryner, B.C., Abraham Lincoln in Peoria, Illinois (1924; reprt., Henry, IL: M and D Printing, 2001). (The author is grateful to Caryl Steinke Schlicher, his sister-in-law, for the gift of this book.) Corbett, Edward P.J., and Robert J. Connors, Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 17–22. The late Dr. John Heissler, professor of English at Illinois State University, introduced me to Corbett and Connors' work, which is available on Amazon.com in various editions and is a widely used contemporary text for reference and instruction in classical rhetoric. Douglas, Stephen A., http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_A._Douglas Guillory, Dan, "Statues with Soul: The Lincoln Bronzes of Sculptor John McClarey," http://www.lib.niu.edu/2005/ih050708.html Henson, D. Leigh, A Long-Range Plan to Brand the First Lincoln Namesake City as the Second City of Abraham Lincoln Statues Henson, D. Leigh, "A Tribute to the Historians and Advocates of Lincoln, Illinois," http://findinglincolnillinois.com/historians.html, includes information about James T. Hickey, Lawrence B. Stringer, and Raymond Dooley. Information about E.H. Lukenbill appears at http://findinglincolnillinois.com/memoirofpostville.html#ehl. Mr. Stringer and Mr. Lukenbill rest on the outskirts of Lincoln, Illinois, in Old Union Cemetery. Mr. Hickey rests in the adjacent Holy Cross Cemetery. The late Mr. Raymond N. Dooley spent his retirement in Arizona. He passed away in 1991 and rests a few miles north of Lincoln in Funks Grove Cemetery near McLean, with his devoted wife Florence Dooley. Funks Grove is just south of Bloomington, Illinois, where Dooley was born and raised. Henson, D. Leigh, A Long-Range Plan to Brand the First Lincoln Namesake City as the Second City of Abraham Lincoln Statues Henson, D. Leigh, “Classical Rhetoric as a Lens for Reading the Key Speeches of Lincoln’s Political Rise, 1852–1856," http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0035.103/--classical-rhetoric-as-a-lens-for-reading-the-key-speeches?rgn=main;view=fulltext Henson, D. Leigh, curriculum vitae, https://findinglincolnillinois.com/DLHensoncv7-23.pdf Henson, D. Leigh, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/leigh.henson, and LinkedIn, http://la.linkedin.com/pub/d-leigh-henson/16/1a5/923. This LinkedIn site has my various articles and other posts relating to Lincoln.

Henson, D. Leigh, play script The

Re-Enactment of Abraham Lincoln's Hickey, James T., The Collected Writings of James T. Hickey (Springfield, IL: the Illinois State Historical Society, 1990). Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association website, https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/jala/ Lehrman, Lewis E., Lincoln at Peoria, The Turning Point: Getting Right with the Declaration of Independence (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008). John L. Lupton's review of Lehrman's book on the Peoria speech published in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0031.109/--lincoln-at-peoria-the-turning-point?rgn=main;view=fulltext Library of Congress, Digital Collections, American Memory, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html "Lincoln Family Sculpture Unveiled in Springfield," http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/news/looking.htm Lincoln Heritage Museum of Lincoln College, Lincoln, Illinois, https://museum.lincolncollege.edu/ Papers of Abraham Lincoln, https://papersofabrahamlincoln.org/ Sorensen, Mark W., "The Illinois State Library: 1818--1870," http://www.lib.niu.edu/1999/il990133.html Stringer, Lawrence B., Logan County, Illinois: A Record of Its Settlement, Organization, Progress, and Achievement, Vols. I and II (Chicago: Pioneer Publishing Company, 1911). |

|

Email comments, corrections, questions, or suggestions.

|

|

"The Past Is But the Prelude" |

|

|

|

|